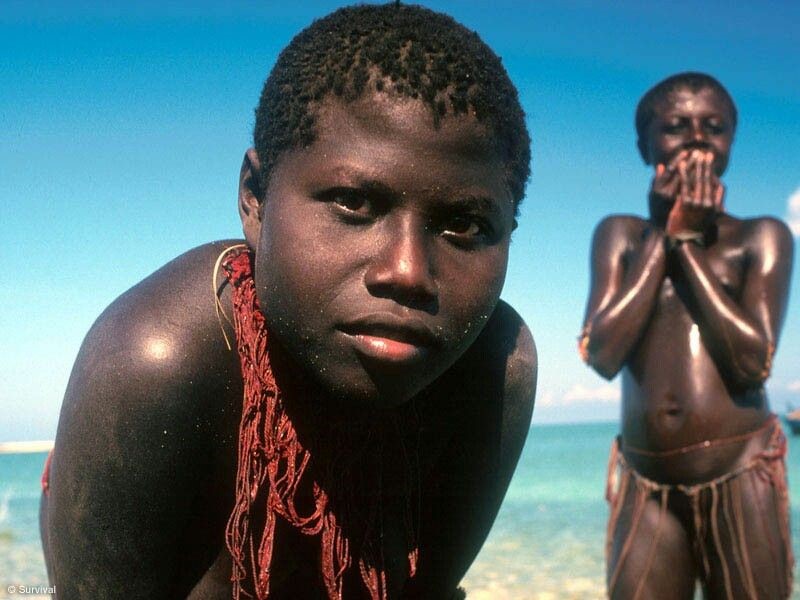

JARAWA, ANDAMAN

(Source)

While they do not hate modern population as much as the Sentinelese, they are still rooted in their tribal customs and traditions. Unfortunately, the building of the Great Andaman Trunk Road has resulted in a lot of exploitation of the tribes by tourists and modern local societies. The Jarawas are pretty weird when it comes to food though. They relish fish, pigs and other animals but wouldn't touch a deer, which the area is highly populated with. Perhaps they consider deer sacred. Also, the tribal people of Jarawa change the names of their children post puberty. There is an elaborate ceremony held to celebrate, in which a boy has to hunt a wild pig and offer it to everyone in the village, and a girl is anointed in clay, pig oil and gum, post which the children are given their new names. The tribals are also aware of contraceptive policies and use herbs and plants as contraceptives! (Source)

INTRODUCTION

The Jarawas (also Järawa, Jarwa) (Jarawa: Aong, pronounced) are an indigenous people of the Andaman Islands in India. They live in parts of South Andaman and Middle Andaman Islands, and their present numbers are estimated at between 250–400 individuals. They have largely shunned interaction with outsiders, and many particulars of their society, culture and traditions are poorly understood. Since the 1990s, contacts between Jarawa groups and outsiders grew increasingly frequent. By the 2000s, some Jarawas had become regular visitors at settlements, where they trade, interact with tourists, get medical aid, and even send their children to school. The Jarawas are recognised as an Adivasi group in India. Along with other indigenous Andamanese peoples, they have inhabited the islands for several thousand years. The Andaman Islands have been known to outsiders since antiquity; however, until quite recent times they were infrequently visited, and such contacts were predominantly sporadic and temporary. For the greater portion of their history their only significant contact has been with other Andamanese groups. Through many decades, contact with the tribe has diminished quite significantly. There is some indication that the Jarawa regarded the now-extinct Jangil tribe as a parent tribe from which they split centuries or millennia ago, even though the Jarawa outnumbered (and eventually out-survived) the Jangil.The Jangil (also called the Rutland Island Aka Bea) were presumed extinct by 1931

Origin

The Jarawas have been around for a long time. They are believed to be descendants of the Jangil tribe and it is estimated that they have been in the Andaman Islands for over two millennia. The Jarawas were both linguistically and culturally distinguished from the Greater Andamanese, who did not survive over the years. The early colonisations by the Jarawas showed evidence that there was an early movement of humans through southern Asia and indicate that phenotypic similarities with African groups are convergent. They are also believed to be the first successful tribe to move out of Africa. Any form of evidence on the Jarawas—social, cultural, historical, archaeological, linguistic, phenotypic, and genetic—support the conclusion that the Andaman Islanders have been isolated for a substantial period of time, which suggests why they have been able to survive despite modernization. The Jarawas are one of the three surviving tribes in the area, the other two being Sentinelese and Onge. This triad is connected with the Greater Andamanese language clade on a typological—rather than a cognatic—basis, suggesting a historical separation of considerable depth.

Hunting and Diet

As the Jarawas are a nomadic tribe; they hunt endemic wild pigs, monitor lizards and other quarry with bows and arrows. They have recently begun keeping dogs to help with hunting, as the Onges and Andamanese do. Since this is an island tribe, food sources in the ocean are highly important to them. Men fish with bows and arrows in shallow water. Women catch fish with baskets. Mollusks, dugongs and turtles are a major part of the Jarawa diet. Besides meat and seafood, Jarawas collect fruit, tubers and honey from the forest. In order to get honey from bees, they use a plant extract to calm the bees. The Jarawa bow, made of chuiood (Sageraea elliptica), is known as "aao" in their own language. The arrow is called "patho". The wooden head of the arrow is made of Areca wood. To make the iron head arrow, called "aetaho" in their language, they use iron and Areca wood or bamboo. When they go hunting or on raids, they wear a chest guard called "kekad". Food preparation is mainly done by roasting; baking as well as boiling. However, the Jarawas also consume food raw. The Jarawas have well balanced diets, and since they exploit both terrestrial as well as aquatic resources, they can easy supplement one type of food by another one in case of a shortage. The Jarawas also have support from the Indian government. They receive monthly allowances by the government and also receive wages for taking care of citrus fruit plantations. The Jarawas have a strong dependence on gathering different items, such as turtle eggs, honey, yams, larvae, jackfruit and wild citrus fruits and wild berries.

Impact of the Great Andaman Trunk Road